Studio Visit & Interview with Humberto Maldonado

By John Vochatzer

If there is currently any tour-de-force of an artist in the Bay Area art scene that has come seemingly out of nowhere, it’s Humberto Maldonado. Growing up in a Mexican migrant family not too far away in the Central Valley town of Livingston, CA, Humberto received their BFA at Stanislaus University in the nearby city of Turlock just a few years ago in 2019. A year and a half later, in the fall of 2020 and at the height of a global pandemic, they found themselves here in San Francisco which they now call home. Working out of a live/work space in the Inner Mission District, Humberto makes work that is very Mexican, very queer, and most of all very honest— to the point of intensity.

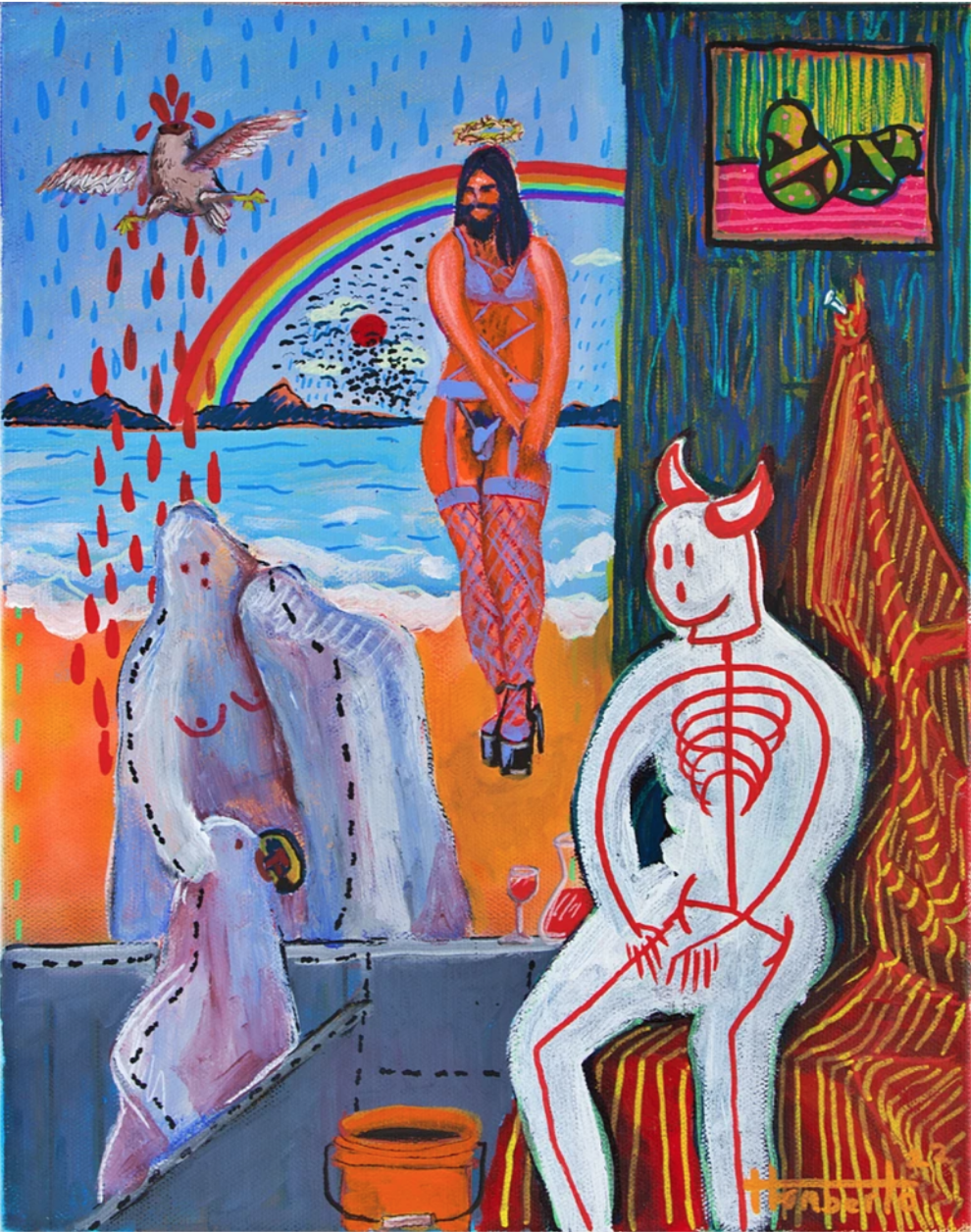

Humberto works mainly with acrylic, but the paintings are by no means limited to one medium and occasionally include clay sculpture and found objects which transport them almost into the realm of assemblage art. These items may often hold the function of accessories or even talismans, just as the central figures themselves do, in the greater cultural narratives Humberto presents in their work. It’s this contrast between individual and collective identity, and all of the liminal spaces therein, that sets the framework for Humberto’s beautiful and at times somber inner world navigated in their art.

Likewise, personal and collective trauma are also topics deeply explored in Humberto’s paintings, which are both expressionistic and anecdotal in nature. Never shying from the difficulty of these topics, Humberto instead has bravely and humorously built an entire visual language upon them. With a signature dark, and often self-deprecating sense of humor, handed down to them by their grandmother Mami Chayo, Humberto’s work is like the perfect tragicomedy—overflowing with dreamlike symbolism and strong notes of Latin American Magic Realism.

One of the more recent and defining developments in Humberto’s trajectory as a young artist would be their sabbatical from art that took place throughout the majority of 2020—a year off with the intention of deconstructing the dogma ingrained in them in University, and of combating the colonialism and hegemony of western ideals that permeate the academic art world. Humberto’s work since has embraced a more primitivist approach to painting; raw and intuitive but without ever compromising their inherent skillfulness. This advancement in Humberto’s work is the full embodiment of learning the rules only in order to break them, and they do so in a way that is again both uniquely personal and culturally resonating.

But ultimately what really makes Humberto’s work so strong is the stories it tells—which are both Humberto’s own story, and the more universal stories—like those of being queer and being a migrant and the feeling of being transplanted and outcasted in an often hostile society. And what makes it accessible is the humor and the wit that they use to guide us, the viewers, through it all.

Interview

Hey Humberto! Thank you for letting me come check out your studio and see all the great stuff you’re currently working on. You’re pretty new to the San Francisco art scene, so for those who don’t know you can tell us a little bit about who you are and how you ended up here in SF?

Thanks for coming over! I am super excited to have a studio space in SF after years of dreaming about moving to the city. As a Mexican-American painter, San Francisco has always attracted me for its rich art culture steeped with Mexican influence! My journey to San Francisco was 50% planning and 50% happenstance. Before the pandemic I had just graduated from art school and had started to plan the move to San Francisco, and the pandemic actually accelerated things and made a move happen a lot sooner. I had planned to move to San Francisco to pursue my artist career, and am thrilled that is what I am doing now.

You grew up in The Central Valley, in a town called Livingston, near Merced. Can you tell us a little bit about what growing up there was like? And how did it shape you as a young artist and as who you are now?

Growing up in Livingston was such a colorful experience, mostly because of the migrant farmworker population that my family is a part of. I think the town influenced me with the concept of storytelling. Storytelling has a large role in maintaining and celebrating culture and identity, and I grew up with the campesinos (farmers) in Livingston telling vibrant stories of their homeland in Mexico. The migrant people in Livingston taught me how to tell a story and be proud of my Mexican heritage, and I now use this tool in my paintings. I consider myself to be a narrative storyteller through figurative painting.

Your work can deal with a lot of very intense subject matter, but it’s often balanced with humor. You talked a little about how this sense of “taboo” humor is something that you got from your grandmother. Can you expound on this type of humor a little bit? And can you tell us a little bit about who your grandmother was and what she meant to you?

Yes, most of my work does deal with dark humor but that's because comedy is the best way to talk about a difficult subject. My humor directly comes from my grandmother, Mami Chayo. She was always a beacon of light in the darkest room. She always cracked jokes about her cancer and the hardships she had when dealing with racism and abuse. I think a perfect story to give a good representation of my grandma's humor would be when she got diagnosed with cancer. When the doctor told her she had cancer she responded with ”but I'm a Sagittarius.” That's really how she dealt with trauma. She was a crazy old lady and she knew it but never left anyone without leaving them a smile. I am a lot like her and she is the main influence in how I approach handling tough subject matter in my art. I always enjoy giving smiles and making fun of my traumas.

Before moving to SF you received an education in art at Stanislaus State— how did your education further shape or affect your growth as an artist?

I feel like Stanislaus really helped me by pushing me to create more original works. But I guess what I really learned was how to speak up for myself and try to speak up for others who are not able to. The majority of the faculty teaching while I was there was mostly cis white men and there really wasn't any representation or a safe place for POC and queer people. That really drove me to create a safe space in the form of the Queer Art Collective, which is still active today. This is where the students are able to be themselves and not be ashamed to be visible. Stanislaus taught me to be a voice for myself!

Perhaps the most over-arching themes in your work deal with your identity as a queer and indigenous individual. What has this experience been like for you? And how do you express it in the work you create?

My identity is very strong in my work because growing up I was pushed to hide my identity and hide who I was. As a mestiso (mixed) queer brown kid, I had to learn to be someone who I didn't want to be. There was so much hate surrounding who I was that I became something fake and I feel like I have lost so much of my identity that now I want to bring it back. Currently, I allow myself to see these parts of me on a surface where I can reflect. I express my self identity in the view of what the child me would have loved to have seen themselves as; free to live in their own skin.

A lot of your work also, as you explained, has to do with your experiences as a migrant person, and the feeling of having been transplanted here in California. Can you tell us more about this aspect of you and your art?

Yes, coming from a migrant family, it can be difficult to feel like you are a part of something because you are not really a part of your homeland and you are not truly seen as American. I see myself as transplanted, kind of like a propagation or a seed growing from a different country here in foreign land. I feel like I show this in my work in the literal form by painting propagations and sprouts of random plants growing in different parts of the land, but also with the figures not always fitting comfortably. There is something uncomfortable in the way the figure rests in the environment, and you can tell the figure doesn't really belong where they're placed.

Almost all of the work of yours that I’ve seen is very anecdotal in nature. How do you come up with the narratives and the symbolism that you incorporate into your art?

All the narratives come from experiences or stories told to me. They're very true to life and true to me and my experiences. As for the symbolism, I feel like it's the same. The meaning I put into the symbolic nature of things are from meanings I have attached to objects almost like a fetishization of material things with emotional intent whether it be literal or metaphorical. I also utilize a lot of Mexican-Indigenous symbolism that can be recognized by those familiar with the culture. With my paintings, I usually have a rough idea of what I want to paint - but the story that comes out is unpredictable and I usually have to sit and reflect on a painting once I finish it.

Something I really enjoy about your paintings is all of the adornment and decoration in them, and using the human figures primarily as accessories to the cultural iconography you choose to include. What inspired this element of your work?

When I paint I do use the figure as an accessory to the overall narrative. This is because the cultural artifacts are what really tells the story of who this person is. These objects give the figure its identity, background and a current situation. I think this element of my work was inspired by the question ‘where are you from?” followed by the next question “No where are you REALLY from?” It is kind of a rude question because it highlights the fact that they don't see me as American when I say I am from Livingston CA, they just want me to say I am Mexican. So in my work the cultural artifacts identify where the figure is from.

It was interesting hearing about how you took a year off from drawing and painting, mostly in order to dismantle a lot of the western ideologies that you felt were permeating your work, and how you’ve come to embrace more non-western primitivism since. What was this year off like? And can you elaborate on how it has impacted the art you’re making now?

When going to school I got a traditional classical education when it came to painting. At some point in my life I began to feel ashamed for feeling super colonized and the idea that the western way of doing things is the correct way of doing things. And that way of thinking casted a shadow on my identity. So after I realized that this was also getting in the way of my painting style I decided to take a break from painting and unlearn some of the technical skills I had learned. I still created art not classically, but artisanally. This led me to disconnecting from realism and implanted me into self-expression in attempting to recover some identity I lost. When I got back to painting it became more raw and instinctive.

You have a couple exhibits coming up this fall, including one at the MACLA in San Jose. Want to tell us a little bit about this exhibit and the work you’re going to be including?

For MACLA San Jose, I am a part of a show called “𝘋𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘰 𝘙𝘦𝘣𝘶𝘪𝘭𝘥”, which is open now through November 13th! The exhibition highlights gender identity and focuses on Queer Latinx artists. The pieces that I am showing deal with my queer Mexican identity and the acceptance I received from my grandmother before she passed. There are four pieces in the show and one automatically creates a connection with the other whether it be by symbols, narratives or identity having to do with the deconstructing and reconstructing the identity.

As an emerging artist, where do you want to be taking your work next? And what kinds of resources and opportunities do you think could help you and other queer and indigenous artists on their creative paths?

As an emerging artist, I would love to take my work to those individuals that would benefit from seeing it—this means taking myself international and working with more galleries. There have been times where I share my work and talk about it in the most honest way that I can, and people relate to my stories. They can reflect themselves in my work and make it their own narrative and I think that's where my work belongs, in front of the audience that will benefit from my story. I think that the resources and opportunities I would need to help me succeed in this are more gallery opportunities and showing where the marginalized still stand on the margin. I feel like a lot of queer indigenous POC people brown people would benefit from places that don't use our arts as tokens. I don't just want to fit the minority themes, I want to be seen as an artist that is creating art for art's sake even if the subject matter has to do with my marginalized backgrounds!